The extraordinary story of

Roderick Kenneth MacDonald

Australian War Correspondent

Societies at war – and people with loved ones serving – have always needed news from the conflict. Since the invention of the telegraph, allowing newspapers to receive details from distant battlefields in minutes instead of months, people have used new communication technology to bring the war home to the countries waging it. Telegraph, telephone, radio, the ability to send canisters of film by aircraft – with these methods of transmission, Second World War journalists plied their trade. While we enjoy fast digital communication tools today, the power of word and picture remains the same as ever.

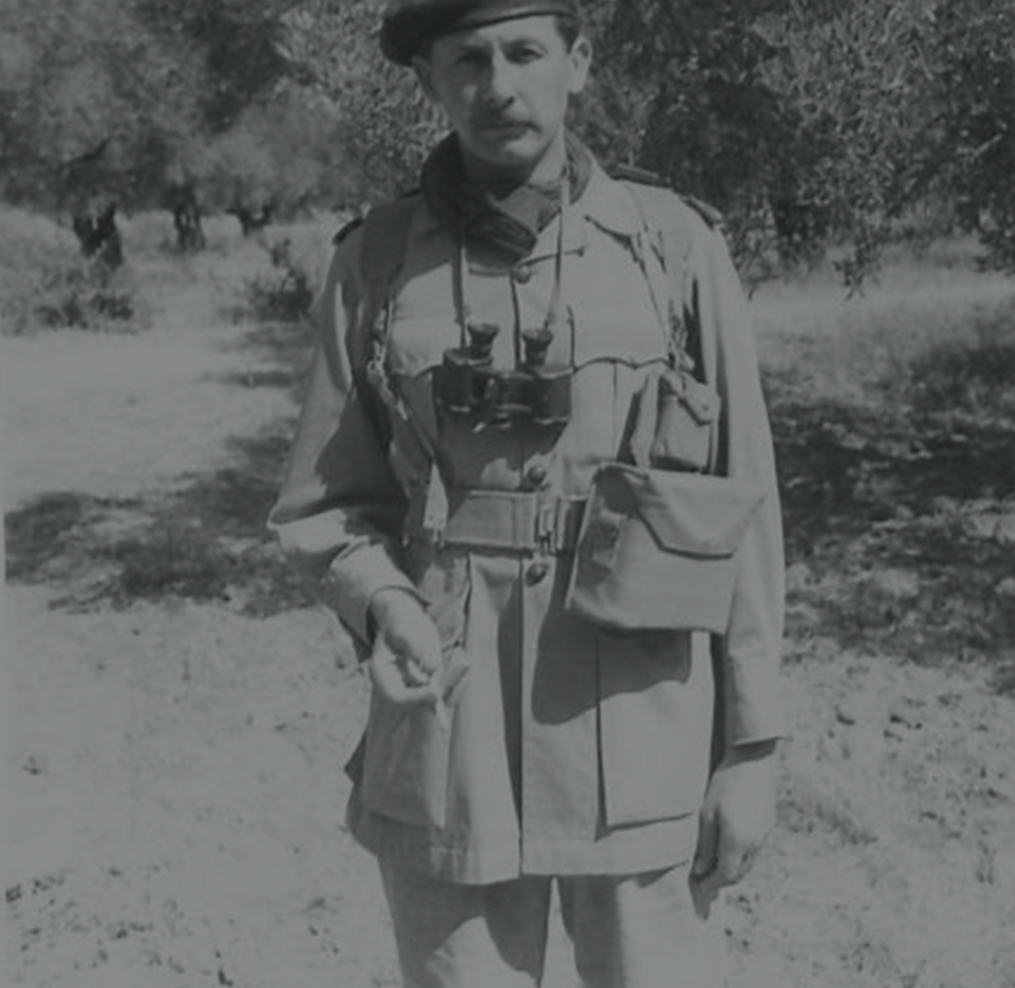

MacDonald in Scotland

Roderick MacDonald, called ‘Ken’ by his colleagues, was born in Scotland in the summer of 1912. He was about 16 months old when he and his parents, Donald and Clarice, emigrated to Australia. His father, a Presbyterian minister, took over the Scots Kirk in Mosman, Sydney, in 1915, staying until 1941 when he resigned to run for a seat in the NSW Legislative Assembly. There was one break in his tenure at the church — he volunteered as an army chaplain during the First World War, serving with Australian troops in the UK and in France, returning in December 1918.

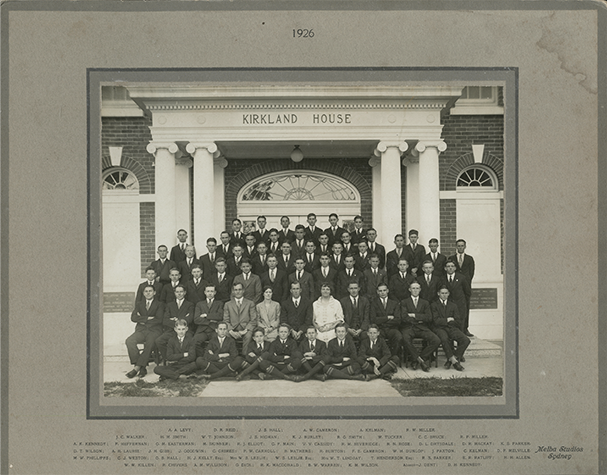

Two daughters joined the family. Ken was educated at The Scots College as a boarder in Kirkland House from 1926-1931. He excelled at English and was published in the school's magazine, going on to the University of Sydney where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts. He joined the Sydney Morning Herald newspaper as a cadet, learning his trade there and then working for other papers in Australia, London and Glasgow. When war broke out in Europe in September 1939 he was with Brisbane's Courier-Mail. In 1941, Ken returned to the Sydney Morning Herald as a foreign correspondent and headed for China; December 1941's Japanese attacks around the Pacific changed him into a war correspondent.

Roderick MacDonald, called ‘Ken’ by his colleagues, was born in Scotland in the summer of 1912. He was about 16 months old when he and his parents, Donald and Clarice, emigrated to Australia. His father, a Presbyterian minister, took over the Scots Kirk in Mosman, Sydney, in 1915, staying until 1941 when he resigned to run for a seat in the NSW Legislative Assembly. There was one break in his tenure at the church — he volunteered as an army chaplain during the First World War, serving with Australian troops in the UK and in France, returning in December 1918.

First, he reported from Singapore, Rangoon, and Chungking, then back to Burma (now Myanmar) and on to India. He was trying to reach the Allied forces in North Africa but had to go via West Africa where he contracted malaria, suffering a very bad case. He joined the Allied armies in Tunisia in January 1943, just in time for the Battle of Kasserine Pass where the tide turned in the Allies' favour, but many weeks of hard fighting would be necessary before German and Italian forces would surrender and the Allies reach Tunis and hold all of the North African coast.

In January 1944, MacDonald published a memoir covering his war

years from 1941 to the Allied success in Tunisia in May 1943. This is an

extract from a chapter covering the costly battle of Longstop Hill in

April 1943 followed by the Allied victory in reaching Tunis. During the

battle for Longstop Hill, having been awake and under fire himself for

twenty-four hours, stuttering when he tried to speak due to exhaustion

and near-misses by bombs and shells, Ken sat down to write:

Having won control of North Africa the Allies could now turn to liberating Europe, beginning with Sicily, with Italy to follow.

In July 1943, Commonwealth and American troops landed on Sicily and MacDonald went with to report on the action. Though a non-combatant, he joined the sharpest end of the invasion - he landed with glider-borne troops ahead of the main seaborn force. He saw first-hand the tough first fifteen hours of the fight for Sicily and was even captured by Italian defenders, but liberated soon after by another Allied unit. By mid-August the island was secured and in early September the Allies landed on the Italian mainland. Mussolini's fascist government had now fallen, but German armies remained in Italy to stop the Allies reaching further into occupied Europe: they slowly withdrew north, destroying bridges, railways and roads. In late December 1943 the painstaking and hard-fought Allied advance halted some 70 miles south of Rome, near the town of Cassino and its mountain, Monte Cassino. From January until May, MacDonald helped to keep the readers of Australian and British papers in touch with the hard fighting taking place there.

“Men here feel that they are not being

appreciated as much as they should.”

-MacDonald's memoir, 1941

On what would be the final day of the Battle of Monte Cassino (18 May 1944), Macdonald was travelling up to the front lines behind the advancing Eighth Army with British reporter Cyril Bewley when their jeep came under German artillery fire. They sought cover in a roadside field where they set off a mine and were instantly killed.

The capture of Monte Cassino opened the route to Rome, but the Allies lost over 50,000 men killed and wounded at Cassino. More than 2,000 of nearly 4,000 Commonwealth servicemen now resting in Cassino War Cemetery died during the final efforts to take Monte Cassino in May 1944. Many of those who would fall in the battles to come are commemorated on CWGC's Cassino Memorial built within the cemetery.

Macdonald and Bewley were initially buried where they fell; their graves were brought to Cassino War Cemetery when it was ready for burials. They lie alongside the brave and tenacious men about whom they had filed stories home – row upon row of headstones tell their stories now. MacDonald's father and mother requested that his be inscribed:

To live in hearts

we leave behind

is not to die.

Roderick Kenneth MacDonald

1912 - 1944

We'd love to hear your story

We use necessary cookies to make our site work. We'd also like to set analytics cookies that help us make improvements by measuring how you use the site. These will be set only if you accept.