The extraordinary story of

Edson Gilroy Armour

434 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force

Every individual who served in the armed forces brought with them their pre-war skills and experience. The military looked for these skills and often placed individuals with technical experience into technical roles. Engineering skills take time and skill to learn and during both world wars the military desperately needed individuals who could undertake a multitude of complex tasks while under fire. From survey defences and building roads, to calculating the fall of shells for artillery and operating complex and cutting edge technology in the midst of battle, these individuals were vital to the war effort.

in Brantford, Ontario, Canada

Edson Gilroy Armour, known as Ed, was born in January 1917 in Brantford, Ontario, Canada. He was the only child of William and Pearl Armour, who raised him in Brantford. Ed was a good student, a promising public speaker and an involved member of Sydenham Street United Church‘s young people’s society. He studied for a degree in mechanical engineering from 1935-1939 in Pittsburgh, USA at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. He then went to work in his father's business, designing heating systems, as he had been doing during holidays while a student.

When war broke out in Europe, Ed wanted to enlist for service in the Royal Canadian Air Force and he applied by letter in October 1939. While waiting for a response, he married Winnifred Matthews in November. He applied again in June 1940 but was found suitable for ground crew instead of what he most wanted: aircrew. He went ahead with enlisting and his technical background qualified him for an officer's commission.

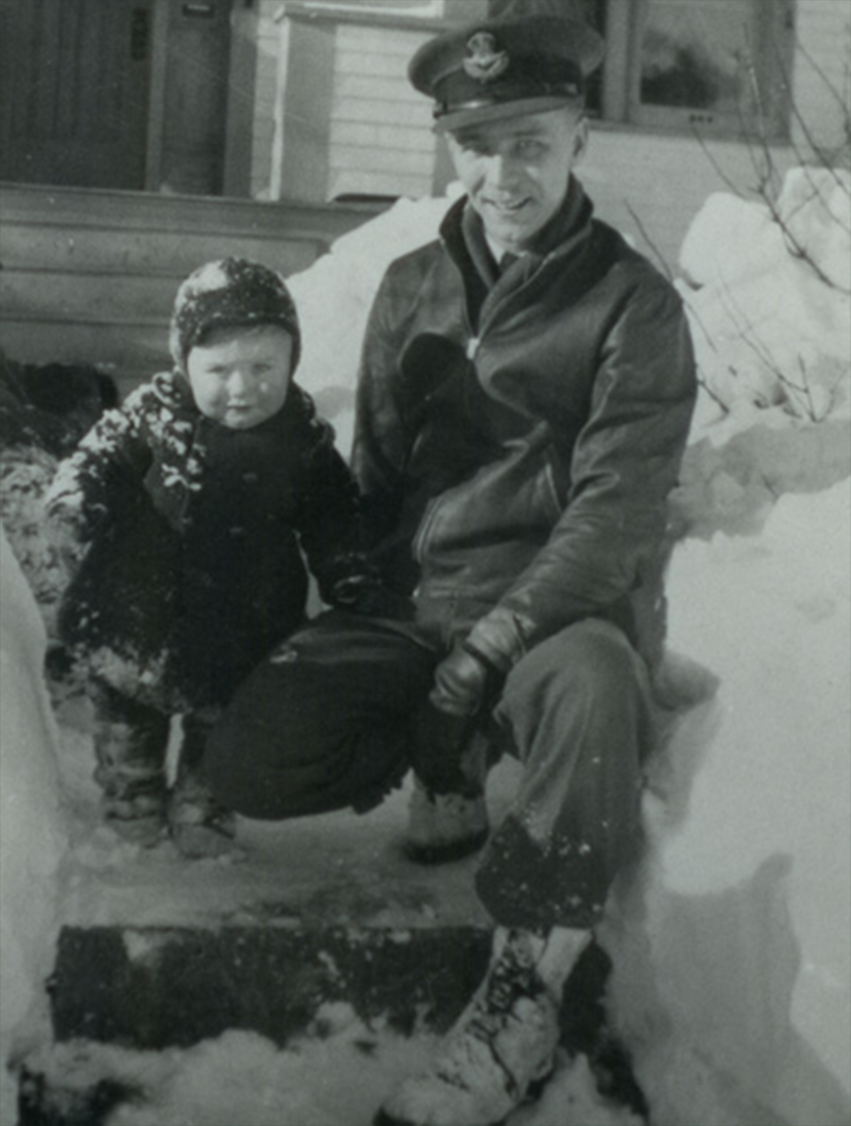

The first part of Ed's war was spent as an operations officer at an RCAF base in Nova Scotia, the largest sea and land plane base in eastern Canada, home of squadrons engaged in anti-submarine warfare in Atlantic waters. Keeping sea lanes open and protected was vital for to the Allied war effort, and Ed's wife and baby son were able to live with him at RCAF Station Dartmouth, but he still wanted to fly against the enemy in Europe and kept requesting to transfer. He finally succeeded in October 1942, qualifying as a navigator in Canada in February 1943. Arriving in the UK in March 1943 he completed operational training before joining No.434 Squadron on 26 October 1943. His crewmates called him ‘the Old Man’ because at 27 he was the eldest, as well as being married with a child.

Their first mission against an enemy target took them to bomb Leverkusen/Cologne in Germany and gave them a sharp initiation into the dangerous world of high-altitude flying, night fighters and 'flak' (anti-aircraft fire). Their aircraft was hit by flak, wrecking Armour's oxygen connection and endangering his life. A crewmate managed to release their bombs over the target and find and hold together severed ends of rubber oxygen tubing well enough to revive Armour and keep him alive as their bomber struggled home to RAF Croft in County Durham. They completed five 'trips' before Christmas 1943, but January-March 1944 would be even busier. When they took off on 18 March it was for their 14th mission to a European target.

In March 1944, Ed and his crewmates had been sent to bomb targets in occupied France four times — rail yards, tracks and rolling stock — important preparation to hobble the German army's response to the Allied invasion of Normandy which would begin on D-Day, 6 June 1944. But on 18 March they were sent on a small diversionary raid, laying sea mines in the Heligoland area of the North Sea, while the main force of over 800 aircraft bombed Frankfurt.

On their return leg they were warned of bad weather developing over RAF Croft. Heavy, low cloud covered the North Yorkshire moors by the time they reached them. Perhaps feeling sure they were well beyond the hills, the pilot descended into cloud only to strike the very last ‘top’ remaining between their position and their base. All on board were killed.

Ed's commanding officer, Wing Commander Chris Bartleft

wrote to Winnifred Armour:

“It is with deep regret that this unit

learned that your husband had been

killed… [he] was not only a valued

Navigator of this Squadron with

but he was highly popular

all ranks”

CWGC commemorates more than 340 men who died while serving with 434 Squadron between August 1943 and March 1945. They are buried in eight different countries and 64 are named on the Runnymede Memorial as they have no known grave. The largest group buried in the UK are in Harrogate's Stonefall Cemetery, where Armour and the other Canadian members of his crew lie side by side. Many more are in our sites in Germany, Belgium, France and the Netherlands where they fell.

His wife inscribed upon his headstone:

THAT WE MAY LIVE

IN PEACE AND SECURITY.

EVER LOVED

BY MOTHER, WIFE AND SON

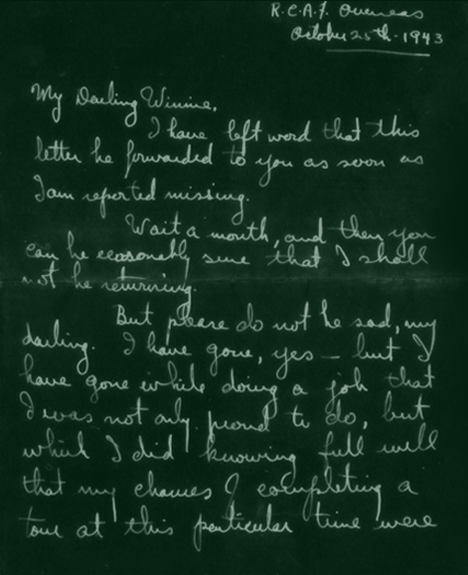

Ed wrote a ‘last letter’ and entrusted it to someone to keep to send

for him if he failed to return for a mission.

Edson Gilroy Armour

1917 - 1944

We'd love to hear your story

We use necessary cookies to make our site work. We'd also like to set analytics cookies that help us make improvements by measuring how you use the site. These will be set only if you accept.